by Anthony Towey

The death of David Bowie has elicited a wide range of reactions—from pensive prelates to caustic critics. For Cardinal Ravasi, he was a kindred spirit in his searching and his suffering. For Giles Fraser in The Guardian, he was a self-obsessed pop idol who deliberately distanced himself from ordinary people and the concerns of everyday life. While one of my colleagues regarded him as a “self-indulgent sh*t,” another is grateful that locals inspired by watching him in a Beckenham pub continue to be the mainstay of the parish music group. I have followed his career from “Laughing Gnome” to “Blackstar.” Part of the problem in trying to offer a balanced assessment of David Bowie is that he spent a goodly part of his artistic energies trying to keep everyone off-balance.

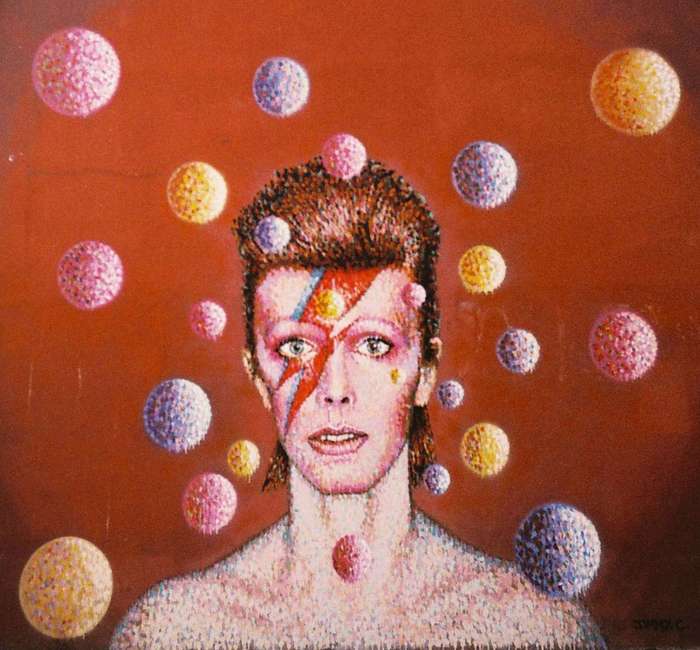

Undeterred by his ordinary name and background, David Jones was clearly a narcissist of the first order, a poster-boy for fans of the Enneagram, Type Four. Feeling innately “special” and “aesthetic,” the variations of his artistic persona may have appeared indulgent but were probably essential for the preservation of his private self and personal freedom. Though Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke might be the most well-known of his creations, his portrayal of the alien in The Man Who Fell To Earth and his lead role on stage in The Elephant Man are more revealing since they articulate the melancholy of non-belonging without the mask of music.

This versatility, however, did mean he could master a range of genres with such originality and integrity that he changed the perceptions of those who listened. Bowie fans who followed him through pop ditties, fantasy rock, indie, soul, electronica, and disco, were being musically catholicized even if they didn’t know it. Even at the height of his notoriety, he managed to bamboozle fans and foes alike by releasing “Little Drummer Boy” with Bing Crosby. Insofar as he broke down the sonic walls that divide schools of music, he was a masterful mediator, a bona fide genius who challenged our prejudice and stands with the greats of his era.

Theologically, Bowie seems to have been similarly eclectic. Brought up by a Protestant father and a Catholic mother, disagreements at home may well have prompted the young David to seek enlightenment and resolution in Eastern traditions, while he remained imbued with Christian fundaments. He flirted with atheism—joking in 2002 that he was just “a couple of weeks” away from “making it.” But despite a typical British reserve about such matters, the religious questions of meaning and destiny suffuse his oeuvre, as his latest work, Blackstar, attests. He hints at his masks being finally removed and if the title track captures where his soul was towards the end, then I can’t help detecting reproach behind the defiance. I suspect it is an act of contrition, voicing a concern that he did not bring light, but darkness.

In terms of justice, I suppose part of the felt frustration is that Bowie was not an agitator for causes in the same way that figures such as Dylan, Lennon, and Sting attempted to be. In Poetry of Purpose, Bernard O’Dowd long ago claimed that the gifted artist should support the socialist cause[1] and for some, the issuing of Bowie Bonds, which commodified his songs, typified the selling out of the rock ʼnʼ roll ideal. However, Bowie did participate in events such as Live Aid and openly admired the zeal of luminaries such as Bono, in part because he knew himself to have a much more circumscribed, less optimistic view of global causes.

Most social commentators would locate his main contribution to justice in the realm of sexual liberation. At a time when British attitudes to homosexuality oscillated between benign buffoonery and outright hostility, Bowie made ambivalent sexuality cool—a full decade before Elton John and others felt able to come out. And unlike Jagger, while he may have eventually settled for the elegance of a New York lifestyle, he remained anti-establishment enough to refuse a knighthood from the Queen.

For me, entering into late life, I remain haunted by “Soul Love” from Ziggy Stardust, which effortlessly calls into question the value of any theology too distanced from experience:

Soul love – the priest that tastes the word and

Told of love – and how my God on high is

All love – though reaching up my loneliness

Evolves by the blindness that surrounds him […]

Inspiration have I none, just to touch the flaming dove

All I have is my love of love, and love is not loving

Defining God as love and not being loving renders God an idol easily depedestaled. For the Christian, the duties of our days should be marked by love—to be otherwise is practical heresy. For myself, I regard Bowie as an artistic genius with a restless soul. I hope he has found peace—but I’m glad I wasn’t in his head!

Dr. Anthony Towey is Director of the Aquinas Centre for Theological Literacy in the School of Education, Theology and Leadership at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, London. He has been singing and writing songs for the whole of his adult life—a compilation Dancing a Straight Line is on iTunes. He is also author of An Introduction to Christian Theology (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2013).

[1] “[The poet] is the Baptist of his epoch, preparing in its wilderness the Way of the Lord […]. I hold that the real poet must be an Answerer, as Whitman calls him, of the real questions of his age, that is to say, that he shall deal with those matters which are, in the truest sense useful, to the people to whom he speaks,” https://www.marxists.org/history/australia/1909/poetry-militant.htm.

Photos:

By Original:k_tjaaa Derived: Peter coxhead [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons.

By RCA Records (eBay front back) [Public domain], via Wikimedia CommonsPhotos: